Episode Transcript

Announcer: Examining the latest research and telling you about the latest breakthroughs. The Science and Research Show is on the scope. Interviewer: While antibiotics save lives, over use of antibiotics can put patients at risk for hard to control infections and deadly diarrhea. I'm here with Dr. Matthew Samore an epidemiologist who researches the best strategies for preventing the adverse effects of antibiotics. Dr. Samore, what are some of the infectious bacteria that are causing the worst problems in hospitals?

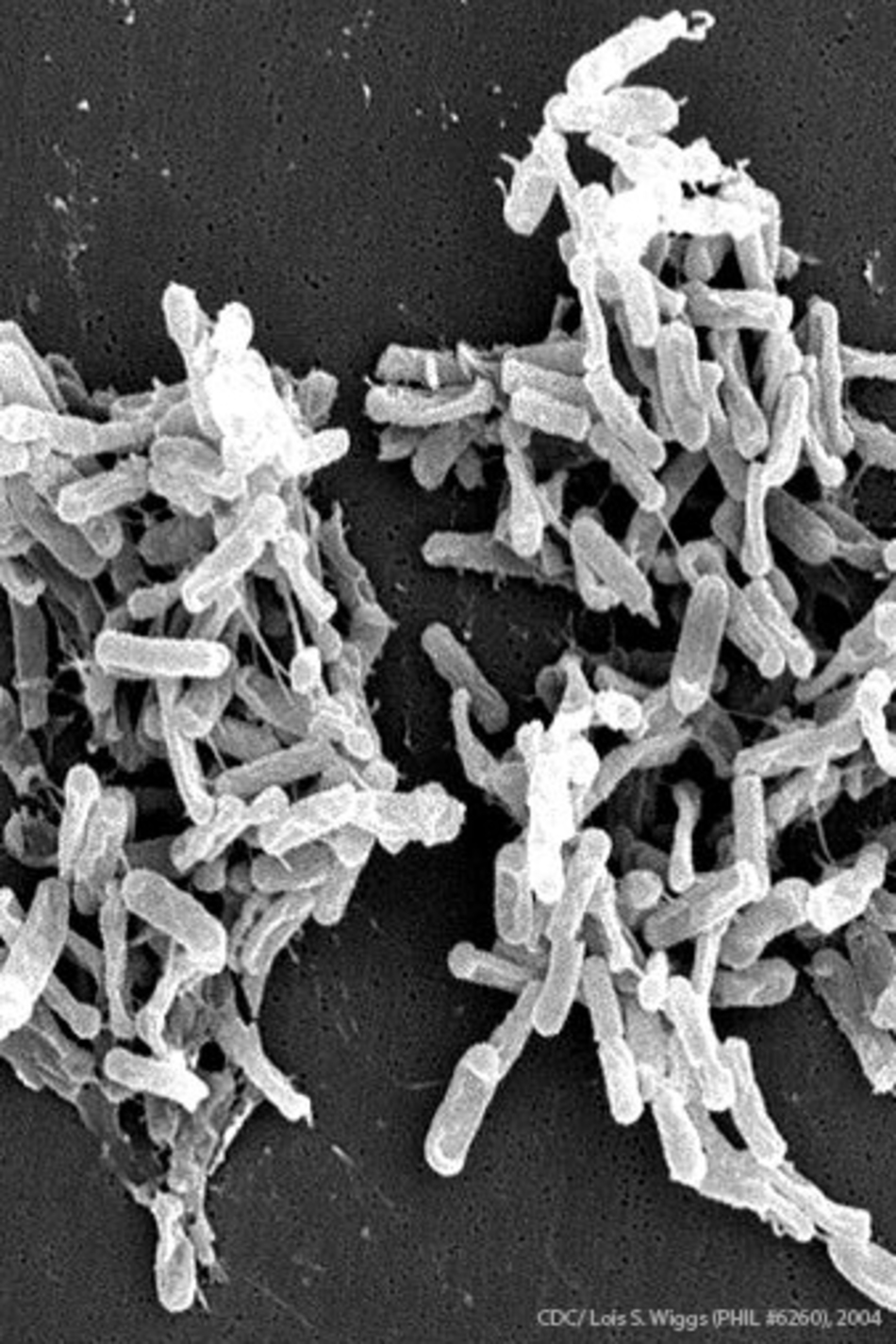

Dr. Matthew Samore: Yes, that's a very good question. Some of the worst offenders in hospital populations are these resistant bacteria. And one that, I'm sure you've heard of that has gained a lot of press is referred to as MRSA or Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. This is a particularly difficult pathogen because it's resistant to many different antibiotics, not just Methicillin, and so the treatment option for this organism are relatively limited. There are actually even worse pathogens than MRSA. There are some gram negative rods that are literally resistant to every drug that we have that's conventionally used to treat infection. And then finally, another type of organism that fits in the same general realm of antibiotic resistance is Clostridium Difficile. And Clostridium Difficile is particularly associated with antibiotic exposure and it causes infection when the normal gut bacteria, what you may have heard of referred to as the microbiome or the microbiota. When that normal gut ecology is disrupted by antibiotics, Clostridium Difficile is then able to take hold into gut. It produces a toxin. This toxin can cause a very severe colitis and at times can be even fatal. Interviewer: You worked at the VA Hospital in Salt Lake City. Have you seen cases of infection here?

Dr. Matthew Samore: Oh, yeah, every hospital. And I'm also at the University of Utah Hospital. By many estimates, Clostridium Difficile diarrhea is the most common healthcare associated infection in U.S. hospitals. It's extraordinarily common and no hospital has succeeded in eradicating this organism. It's simply too prevalent in nature and there is probably no good way at the present to prevent its occurrence completely. Interviewer: You led a study that was incorporated into a report issued by the Center for Disease Control about proper use of antibiotics . . .

Dr. Matthew Samore: Indeed. Interviewer: . . . in combating Clostridium Difficile. Dr. Matthew Samore: Yes, that's the name. Interviewer: Hard to get that out. So what questions were you trying to address in this study?

Dr. Matthew Samore: The CDC has embarked on a series of studies to look at overuse of antibiotics, to look epidemiologically at the relationship between antibiotic use and these adverse consequences like Clostridium Difficile diarrhea. And we had a paper that was published last November in class, one that described a very sophisticated, what we would call a high fidelity model of Clostridium Difficile in hospital populations. And we use that model to examine different kinds of infection control measures to prevent spread of C. Difficile. And that paper caught the attention of CDC. They wondered whether we could apply some similar kinds of modeling techniques to address this question that was raised and their analysis of epidemiological data which was what would happen in a hospital if you reduced high-risk antibiotics. Interviewer: Well, so, you used simulations, you've used models to predict these outcomes. Dr. Matthew Samore: Right. Interviewer: What's the advantage of doing it that way rather than like you talked about before, looking at records, or even I don't know if it's ethical to do the experiment on people. Dr. Matthew Samore: Right. Well, experimentation in people is something that requires an Institutional Review Board approval. Interviewer: Sure. Dr. Matthew Samore: It's obviously a very important part of the advancement of biomedical science and it's something that is vital to ultimately achieve solutions that can actually make a difference. The problem is experiments that are done are often actually not even clear cut in their answers and you can't really examine every possible type of intervention in experiments. And the other challenge that has been particularly pervasive for antibiotic resistance is that most hospitals tackle these problems one at a time or one institution at a time, so often the interventions that are done are not controlled. They're often ambiguous in interpretation and so it actually has been very difficult to get a deep understanding about the consequences of reducing high-risk antibiotic use from just doing the study in hospitals. And one of the things that's interesting and attractive from the scientific perspective is the complexity of spread of infectious diseases and that's where these more sophisticated modeling and simulation methods come into play. Interviewer: So in your simulations, what were some of the parameters that gave you the worse rates of infection?

Dr. Matthew Samore: The effects on transmission have a big impact on disease raids and to the extent that antibiotics increased transmission there is a correspondingly greater reduction in Clostridium Difficile if you reduce antibiotics. So that's an interesting aspect to it I would say. Interviewer: So you mean if physicians administer more antibiotics, you get more infection. Dr. Matthew Samore: That's right. It's a paradoxical thing. Interviewer: Yeah. Dr. Matthew Samore: Right? Antibiotics treat infection, but when it comes to Clostridium Difficile the more antibiotics the wor- . . . The better for Clostridium Difficile, the worst for us. The basic finding was that the predicted fact of reducing high-risk antibiotics by 30% was a 26% reduction in Clostridium Difficile diarrhea. Interviewer: Based on your work and other people's work as well. Right?

Dr. Matthew Samore: Yes. Interviewer: The CDC actually came up with some guidelines for physicians and hospitals. Dr. Matthew Samore: Right. We think and the CDC thinks that achieving a 30% reduction in high-risk antibiotics is possible. Now we think that in general antibiotics should be used smartly. Rather than always choosing the broader spectrum drug, choose a narrow spectrum drug. Stop the drug if it's not needed. If the tests are negative, then stop the drug or maybe wait on empirical use of antibiotics until the tests come back. So there are a lot of ways that antibiotic use can be done more wisely. And believe me a whole other question and we can talk about this in another interview is, how do you change practice?

Interviewer: Yeah, well, I was going to ask that actually. Dr. Matthew Samore: Yeah, it's huge because these patterns get ingrained and they're not the same in the U.S. as they are in other countries. The U.S. is not the worst, but we're nowhere near the best when it comes to appropriate antibiotic use. So the reality is in U.S. hospitals, about half of all patients get antibiotics. And the frequent lament, this goes back a long time, is that antibiotics are used as antipyretics. They're used like Tylenol. Someone has a fever, let's give them an antibiotic. Again, it's because hospitalized patients are vulnerable. They're sick and you probably have heard the adage, hospitals are no place for sick people. The patients are vulnerable. Doctors go on and miss something. To some extent it's a bit of defensive medicine to treat and to sometimes over treat, but the consequences are hazard, exposing hazardous, exposing individuals or patients to these complications like Clostridium Difficile diarrhea. So what we're trying to achieve is an appropriate balance. The adage that we use, what we call antibiotic stewardship is the right drug at the right time, at the right dose, for the right patient. Interviewer: So if hospitals don't abide by these new guidelines, what are you afraid might happen?

Dr. Matthew Samore: The worse case scenario is indiscriminate use of antibiotics leads to a proliferation of antibiotic resistant organism and we just achieve much worse control of infectious disease, and we get into a situation where people are dying from infectious diseases and not being able to be effectively treated. There is not an inexhaustible supply of antibiotics. This is a resource that we share that we should preserve. People think they're safe, you just add them to your water, or just pop a few pills that I left over in my cabinet, but that is not the case. Antibiotics have potentially serious consequences, so they should be used wisely. Announcer: Interesting, informative, and all in the name of better health. This is the Scope Health Scientist Radio.