Read Time: 2 minutes

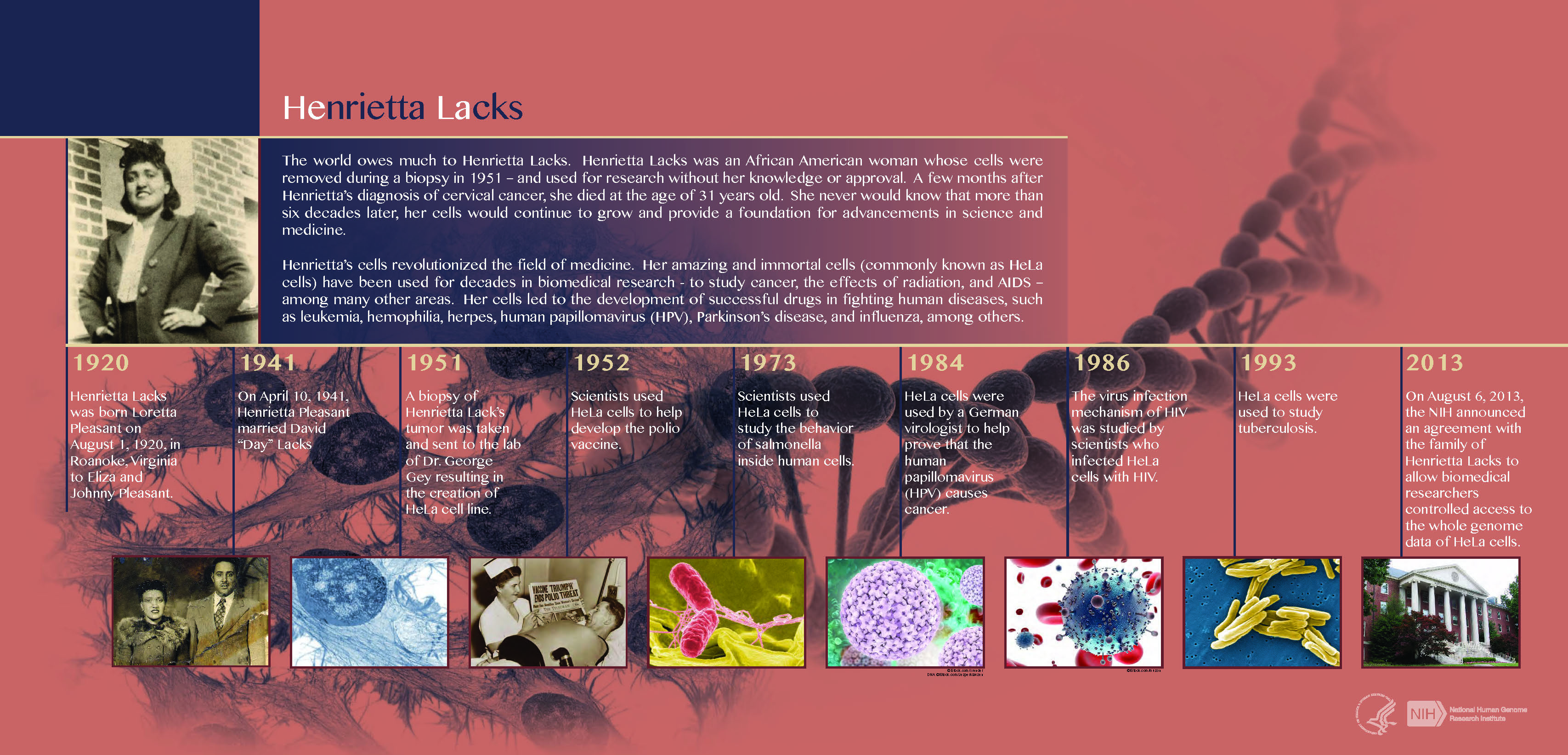

In 1951, a Black woman named Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital to have a doctor look at a “knot” in her womb, which turned out to be cervical cancer. Her doctor took two biopsies, one of cancer cells and one of healthy cells. The cells were taken without Lacks’s knowledge or consent.

Lacks’s cells ended up in the lab of cell biologist Dr. George Gey. Because of a mutation, her cells were able to survive and reproduce outside the body. Dr. Gey grew the cells continuously in the lab, something that had never been done before.

Named after the first two letters of her first and last name, HeLa cells were used in many different medical experiments because they could be grown so easily in the lab. HeLa enabled the development of in vitro fertilization, the first clone of a human cell, the development of the polio vaccine, advances in gene mapping, and more.

The acclaimed nonfiction book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot tells Henrietta Lacks’s cancer story and the revolutionary research, ethical questions, and racism wrapped up in the use of her cells. Previously, very few people knew the source of HeLa cells. The book introduces us to the woman who helped change modern medicine. It also considers the ethical dilemmas of using patient cells without knowledge or consent, the way race played a part in how Lacks was treated, and the impact on her family decades later.

Visit Huntsman Cancer Institute’s Cancer Learning Center to learn how you can check out The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and find more resources about cancer.

Image courtesy of NIH. Click to view full-sized image.