The Mountain West is known for its natural beauty and unique landscapes, drawing many residents to year-round recreation such as hiking, biking, skiing, and fishing. These outdoor activities also mean extended sun exposure at high altitudes—a risk factor for skin cancers, including melanoma, the deadliest form.

In the five-state region Huntsman Cancer Institute serves—Utah, Nevada, Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming—melanoma is among the top four most commonly diagnosed types of cancer. In Utah specifically, melanoma is the third-most diagnosed cancer, with 1,610 estimated new cases in the year 2021.

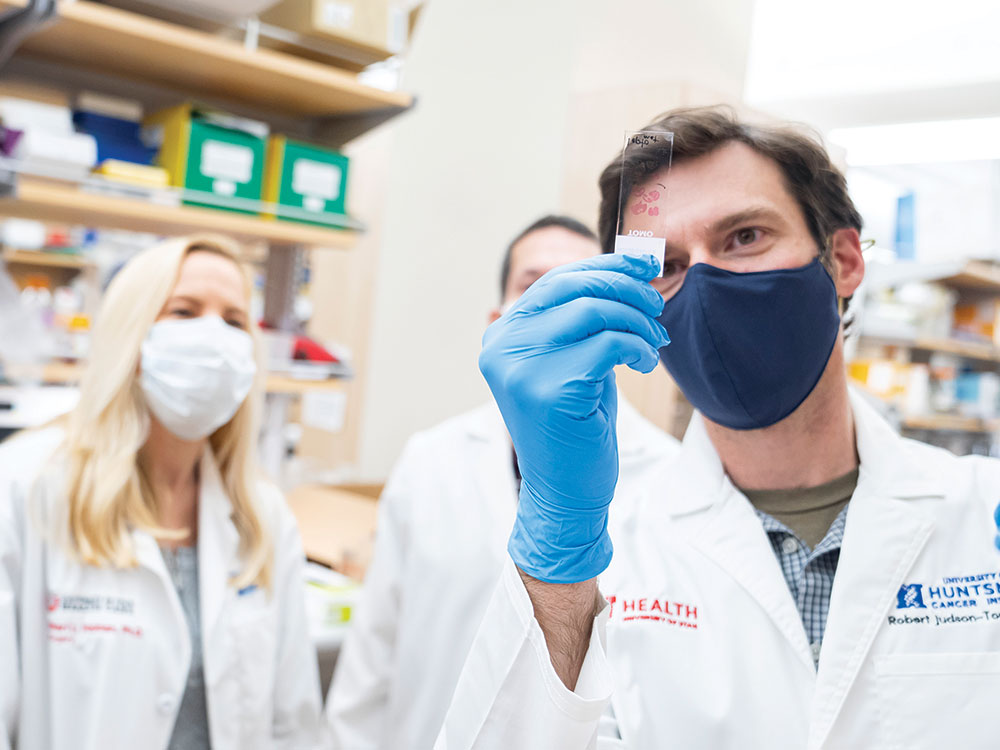

Melanoma originates in melanocytes, the cells that give color to the skin and protect it from sun rays. Melanocytes were thought to be interchangeable, but new research in the Judson-Torres Lab at Huntsman Cancer Institute shows there are, in fact, different types. The findings were published in the September 2021 issue of the journal Nature Cell Biology.

"I noticed that not all melanocytes respond to signals from surrounding cells in the same way," says Rachel Belote, PhD, postdoctoral fellow in the Judson-Torres Lab. "If melanocytes from the same piece of skin respond differently to the same stimuli, this would mean there are actually different types of melanocytes."

The research team took a deeper look at melanocytes—through aging, anatomic locations, sexes, and skin tones. This enabled them to generate a map of melanocytes across the human body and through various stages of cell development.

"We also focused on single-cell resolution, studying cells one at a time," says Robert Judson-Torres, PhD, Huntsman Cancer Institute researcher and University of Utah assistant professor of dermatology and oncological sciences. "The combination of these variables—specifically studying human developmental stages at different anatomic locations with single-cell resolution—permitted us to make the discoveries we did."

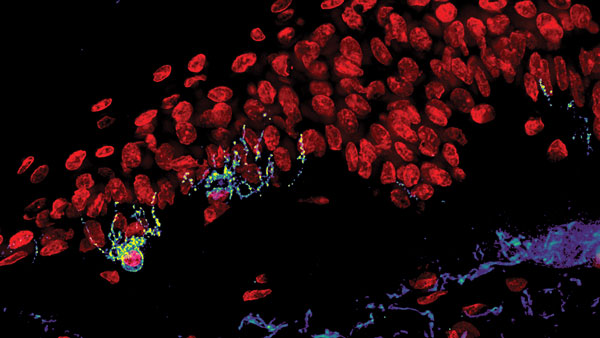

One of those discoveries was a new melanocyte that appears to be the cell of origin for a specific subtype of melanoma called acral melanoma, the most common type in people with darker skin. Currently, very few treatment options exist for this type of melanoma. Judson-Torres says the classic approach has been to first find treatments for more common subtypes of the disease, then see if the treatment works on acral melanoma.

"This study really locks down that acral melanoma is its own thing," says Judson-Torres. "We expect these findings to change how acral melanoma is approached and studied, and we hope it will rapidly lead to acral-specific therapeutics."