The new Utah Retinal Reading Center at the John A. Moran Eye Center plays a pivotal role in the development of therapies.

In 1792, while teaching at Cambridge University, William Farish forever changed the academic world.

Paid by the number of students he could teach, Farish devised the A to F numeric grading system to measure student progress and ultimately increase class size. His system is now a universal yardstick, understood worldwide.

At the John A. Moran Eye Center’s new Utah Retinal Reading Center (UREAD), which opened in early 2020, a talented team is developing universal grading systems of its own.

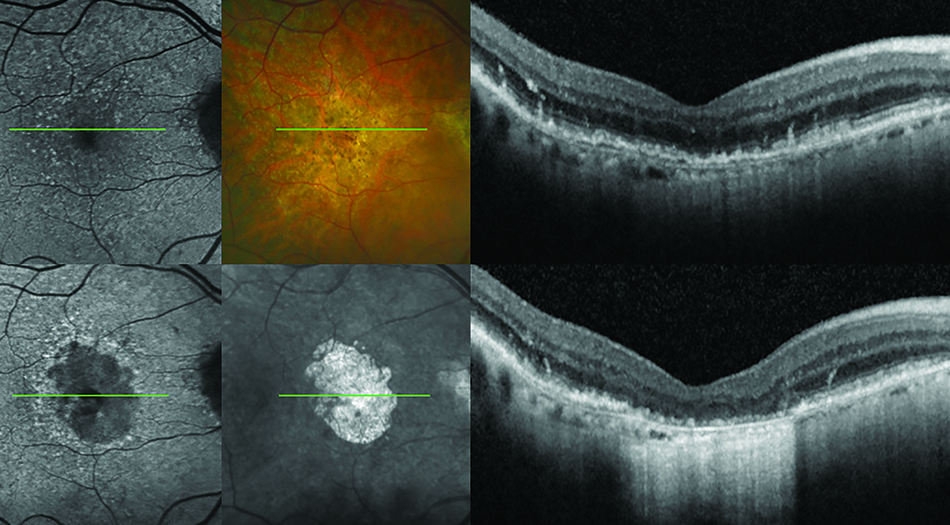

Analyzing thousands of images of the human retina in a process known as "grading," the team is investigating imaging standards that will allow scientists around the world to monitor the progress of eye diseases and the impact of treatments. Supported by a cadre of human image readers and sophisticated image analysis software, UREAD is at the forefront of a rapidly evolving field in which scientists are striving to create a common language in the fight against blindness.

"This is the work that ultimately decides key questions such as the right time to administer therapies and what data points we should be looking at to determine how effective those therapies are," explained UREAD Director Steffen Schmitz-Valckenberg, MD.

Making the Grade

Image graders at UREAD review up to 150 high-resolution image sets of the retina each day, answering unique sets of questions about each based on observations and measurements. They must work independently of each other, looking through up to 200 layers of images that constitute a complete retinal scan.

A majority of the work relates to the leading cause of blindness for adults over age 55: age related macular degeneration (AMD). Schmitz-Valckenberg is a world-renowned physician-scientist and AMD expert who has spent years developing universal standards as private companies and public institutions race to develop a cure for this devastating condition.

UREAD is assisting the Sharon Eccles Steele Center for Translational Medicine (SCTM) to begin clinical trials of a new therapy for AMD. The effort is now combing through more than 12,000 patient visit image sets, analyzing factors such as how different layers of the retina degenerate in various stages of AMD.

For example, one layer might show the earliest changes in thickness, indicating imminent vision loss, or there may be other features present indicating protective effects against rapid disease progression.

The Big Picture

UREAD stands as the only center of its kind in the Mountain West, and since its opening has grown rapidly to take on a variety of collaborations and projects. Among them is an international effort to create a new classification system of early atrophy in AMD. Schmitz Valckenberg and University of Melbourne Professor Robyn Guymer, MBBS, PhD, are coordinating data collection and analysis among six world-leading reading centers, including UREAD.

Regardless of the goals of each project, Schmitz-Valckenberg sees the big picture: helping patients. A talented retinal physician and surgeon, Schmitz-Valckenberg stresses UREAD’s enormous potential to aid the development of therapeutics and to improve clinical care. Combining telemedicine with independent assessment of imaging data could improve the quality of care. In the world of clinical trials, he envisions reading centers in different time zones collaborating using common standards to speed up global studies—and new interventions.

Schmitz-Valckenberg points out an unmet need to process increasing amounts of information produced by rapidly advancing retinal imaging technologies. That’s where reading centers and artificial intelligence strategies must come in.

"Reading centers have the infrastructure and resources to develop faster, more efficient ways to process patient information," he said. "I’m confident reading centers will continue to expand their essential role in ophthalmology."