Episode Transcript

Announcer: Discover how the research of today will affect you tomorrow. The Science and Research Show is on The Scope.

Interviewer: It's not every day that you find a scientist who is training includes time spent in Hollywood, learning how to make animated movies. But Dr. Janet Iwasa, a Professor in Biochemistry at the University of Utah has done just that. She creates colorful and lively innovated movies of the inner workings of the cell giving life to processes that are usually left to the imagination.

Why animated movies? How do you think that changes science?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: I think the power of animation lies in a few different places actually within the research sphere. The first is when you're creating an animation it really requires you to think about things a lot more deeply than I think people typically do when they draw things out. So usually researchers are visual, but they have kind of limited tools by which they can draw the kind of molecular mechanisms that they study.

Typically people draw very static two-dimensional illustrations with circles and squares representing proteins and maybe just kind of one frame kind of thing as their model, which typically represents a pretty complex mechanism that's dynamic. And so taking something like that and putting it in a 3D animation where you can include structural information, information about how things move in space within the context of a cell, including crowding information, all of those things I think add a level of complexity that really makes researchers think harder about the things that they study.

And I think that gives people a lot of ideas. Sometimes it's hard to answer the question of what this should actually look like if we were going to make it three dimensional and moving over time. But I think those are the difficult things that make researchers kind of come to some realizations about some of the things they study. So that's one way I think animation can be really useful just in setting it up and trying to figure out what the animation should look like in terms of just storyboarding the idea.

Interviewer: You've started your career doing research in the laboratory, how did you make the transition to animation?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: When I was a graduate student one of the labs that was next door to mine, they studied a protein called kinesin that walks along microtubules that's kind of the highway in the cell. And prior to that I had seen a lot of meetings where people presented their data on how they thought kinesin walked. And I thought I totally understood what was going on, and then the professor there hired an animator, once they had gotten enough information to really understand what was going on, he hired an animator to create this animation of this protein kinesin walking, this is Ron Vale. And I watched that animation for the first time probably in my second year of graduate school and it made me realize that I didn't really understand how the molecule is moving as well as I had thought I did. And the animation made everything a lot more clear and that was the first time I think I really had seen animation within the research context.

So after that I really became interested in trying to animate the things that we were doing in our own lab. And so I started looking into courses that I could take in graduate school and my professor, Dyke Mullins, he allowed me to take a course that was basically one day a week where I spent the entire day learning animation and creating animations of what my lab studied. And he still uses a lot of these animations now.

Interviewer: And eventually you received some fellowship money to learn some more animation?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: Basically I found a person who was willing to kind of take me on as a post doctoral fellow. That was Jack Szostak of MGH and Harvard, and I created animations on the origins of life with him. And prior to that I kind of figured out some way of being able to give myself a more thorough training in 3D animation; so as part of the fellowship I went to a school called Gnomon, which is located in Hollywood in kind of this warehouse in Hollywood, and learned 3D animation programs a little more thoroughly in the summer before really going to Boston and starting my post doc.

Interviewer: I imagine that you were surrounded by people who were not doing scientific animations. What did they think about what you were doing?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: They thought I was weird. I was definitely the oldest person there. I was 27 and I was by far the oldest person there, as well as the only woman. And in the classes they taught us to model humans and aliens and chairs and things that you'd find in animated movies and not necessarily things that were going to be useful for me when I'm focusing on molecular animation. And so I'd have to think of clever ways of asking questions, thinking about how a virus comes together, a viral shell. I would ask really I think to them weird questions like, say you had a soccer ball and you wanted to take all of the hexagons and pentagons apart and bring them back together, how would you do that? And they'd stare at me and kind of scratch their heads, but they answered me.

Interviewer: Well you probably got them thinking about their animations a little bit differently too, possibly.

Dr. Janet Iwasa: Possibly, yeah. I think I was asking basically for tools that were not premade, so the animation software that I used was really created for animating bipedal things or you know, dogs or cats and things like that; not really for molecular levels of things. So you really have to be sort of clever with the tools that you have available. There are hair systems to animate hair and I've used those to animate molecules. So things like that I think you just have to be a little bit more imaginative.

Interviewer: It seems like a way that, because movies are so colorful and animated and really captivating, it seems like a way that you can capture in an audience, a non-scientific audience who may not ordinarily think about this sort of thing. Have you found it useful in that way?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: I've definitely gotten a lot of comments, especially for the origins of life project. I created this website called Exploring Origins.org as part of that project, and that was really targeting a non-science audience but giving them quite a bit of scientific context as well as really accurate animations. And so from that site I've gotten quite a bit of good feedback, especially from teachers. Teachers tend to be the most vocal, people who have been emailing and thanking me for the materials that I've made available to them.

Interviewer: Now the process you go through is actually very similar to making a regular movie. What's the process you take your collaborators through?

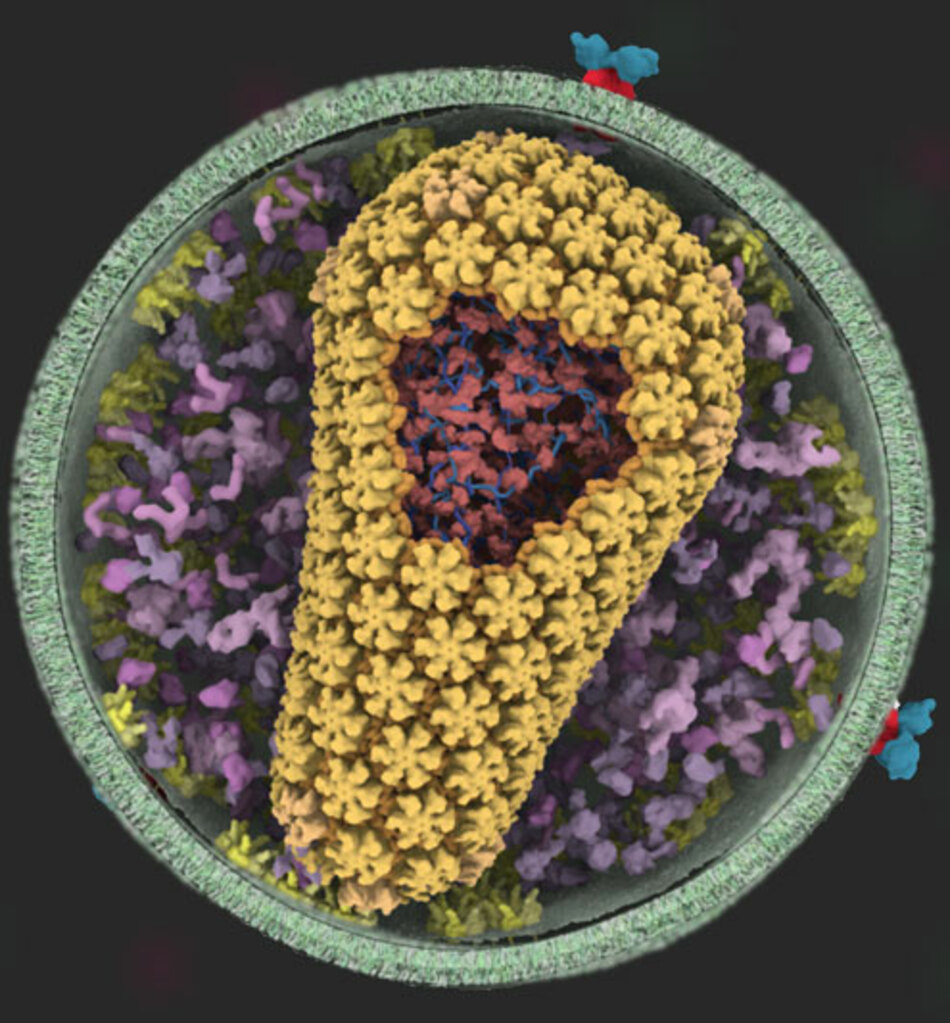

Dr. Janet Iwasa: I think the first thing I usually do is to understand the research. So typically I'm not the expert in the field that I'm doing in animation in, and so I have to rely on collaborators who typically have over a decade's worth of experience within a specific field. And so the kind of literature, for example I'm working on a project on HIV. The literature there is just an astounding amount of literature to have to dig through to figure out even what one protein should look like and act like within the context of the virus. And so I really have to rely on my collaborators to point me to the research that they believe is true and give me those kinds of materials. So that's the first step, usually doing the research and trying to figure out do we know the structure; do we know the what they look like, who are the players.

And then typically after that we draw the story boards, and so there might be a little back and forth with the researchers here, too, in terms of figuring out what should be going on and how crowded things should be; how many of these molecules should be here. And that's typically a hand drawn illustration that shows several of the key frames in any given scene. And that usually happens after that.

And then after that point I usually take things to my computer and start working on trying to create everything in 3D. And then after that there are usually at least five or six drafts that happen for every animation where the researcher, you know, I take comments back and try to tweak the animations to best reflect the research.

Interviewer: So what are a few of the projects that you're working on now?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: The biggest project I'm working on is a project to look at the HIV life cycle. And so this is project in collaboration with a group here called Keta. They are focused on looking at how HIV gets into and out of cells. It's a project that's funded by the NIH, the National Institute of Health.

I think for things like HIV there's been a lot of research; millions and millions of dollars of research of money that's gone into the research. And we actually know really a lot of information about how HIV works. And a lot of these things that research that people are doing is really at the molecular level. But there aren't really many good resources out there in terms of looking at the lifecycle. A lot of things online are actually inaccurate, and so the focus of this is really trying to bring an accurate depiction of how the virus gets into and out of cells. To the public, it's something that people can really start to appreciate how complex this virus is.

Interviewer: And so this website will be available to the public as well?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: Yes, we're hoping to launch probably sometime early next year and we'll have some preliminary animations on there as well as interviews with researchers. I think one of the things that will be kind of interesting to show is how the researchers actually do the experiments. So one of the things I'm planning is doing some video of showing how researchers can figure out the structure of a protein, for example, which is something that a lot of people here in Utah in my department are interested in. And showing that, and also showing an animation of what's going on inside the test tube so you kind of get the macro scale as well as the micro scale, which I think is something that can be hard to visualize.

Interviewer: And what's on the horizon; what are some different things that you'd like to try in the future?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: I have a project called Molecular Flip Book. Currently there really aren't very good tools for researchers to take to really kind of create a 3D animation of what they think molecules are interacting, and I think that's kind of a fundamental thing that every researcher should be able to do, because we have a lot of information that should allow them to do it. But with the tools right now it's quite difficult.

And Flip Book is really trying to take software that people are familiar with, so in this case we're basically creating slides like PowerPoint slides. But instead of just having them 2D and tweening between the slides that are 3D, and you can change the timing between them, so we're trying to take advantage of what researchers are already familiar with, but putting them in a 3D setting.

And so that's software that we're kind of in the alpha version right now, and hoping to have something that's more mature in the next year.

And another thing that I've been thinking about doing again for the researchers is offering a course to sort of allow researchers to kind of see what kind of visualization software is out there. And also to in general try to get researchers to think more about communication and how to communicate better to their peers as well as to the public about their research that they do.

Interviewer: Right, is that something that researchers usually think about?

Dr. Janet Iwasa: There's a lot of variability there. I think there are a lot of people who see the animations as kind of more I can't even than anything else. Or just good for teaching and not necessarily for research, so I think it kind of runs the gamut. But I think there's no question that research is kind of heading in this direction. We need to start visualizing these things better, be it for education or be it for our own research.

Announcer: Interesting, informative, and all in the name of better health. This is The Scope Health Science Radio.