Episode Transcript

Interviewer: Donor matching for fecal transplants, we'll talk about that next on the Scope.

Announcer: Examining the latest research and telling you about the latest break throughs. The Science and Research Show is on The Scope.

Interviewer: I'm talking with Dr. June Round, assistant professor in pathology at the University of Utah. Dr. Round, I think most people have heard about fecal transplant by now, but how effective are they really?

How Effective Are Fecal Transplants?

Dr. Round: So I think people have heard a lot about fecal transplants being for clostridium difficile infections. So they work quite well for this kind of transient infectious organisms.

However, people have started to try them for other intestinal inflammatory diseases like inflammatory bowel diseases, such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease and they are less effective. And I think if we now understand how these microbial communities are shaped will help us to better understand how we can make fecal transplants more effective in the future.

Interviewer: And that's a good segue to your research. You did fecal transplants in mice and got some very different results depending on how they were done.

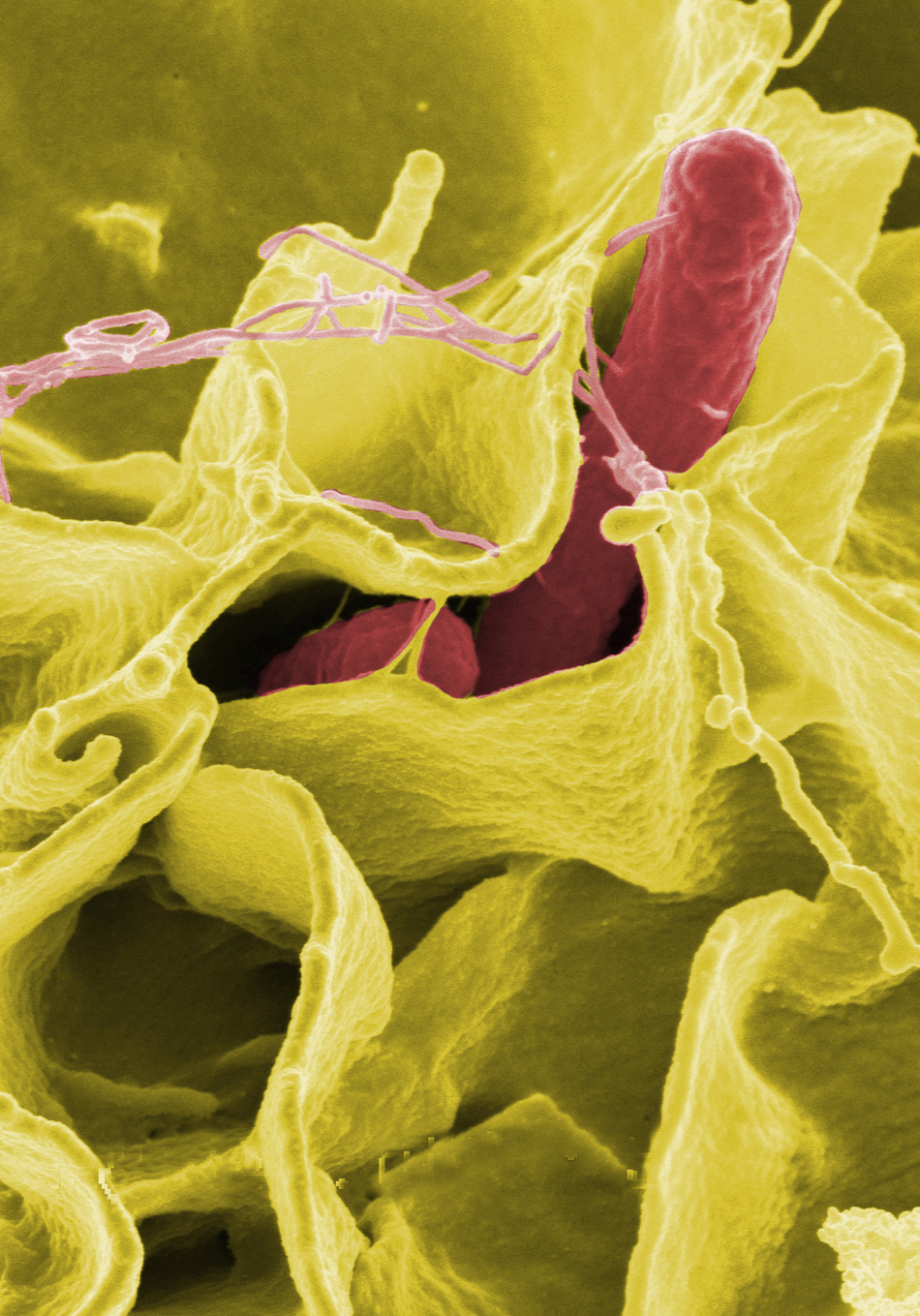

Dr. Round: So we're working with three different strains of mice, so they kind of represent three different people. But you infect them with the same amount of salmonella, which is now a fairly low dose, something that a human might take from contaminated food and some of these animals would dropped dead within two days.

Interviewer: Oh, my gosh.

Dr. Round: Other animals would live well over a week and actually clear the infection, so the differences between the susceptibility or resistance of these animals is really huge. And of course there was the third animal which had a very intermediate response. They didn't drop dead, but they got very sick, had a lot of diarrhea, but eventually cleared it after a couple of days.

Interviewer: This is just sort of their response before the transplant, is that correct?

Dr. Round: That is their baseline response right before the transplant, that's right.

Interviewer: Okay. And then once you did the transplants, what were the differences you saw there?

Dr. Round: So the animal that was highly susceptible, the one that would drop dead after two days after salmonella infection, if you give the fecal transplant from the highly resistant strain, that susceptible strain now became highly resistant. Meaning that instead of dropping dead after two days, it was able to live for well over a week and then clear the infection. So you can essentially make a susceptible animal highly resistant by simply giving it a fecal transplant.

Major Histocompatibility Complex Genes (MHC)

Interviewer: So what was different about these different fecal transplants?

Dr. Round: The difference between the fecal transplants was that they came from animals that had a different suite of immune genes, and these immune genes are called Major Histocompatibility Complex or MHC, so there's lots of these MHC genes. So express multiple MHC genes and the very different throughout the population.

Interviewer: So maybe a little bit like we have different blood types, but more complicated than that.

Dr. Round: That's a great example.

Interviewer: Do your findings suggest that people with a certain MHC profile will always combat certain infections better than others?

Dr. Round: The major point of our paper is really that your MHC type dictates the type of microbes that live on your body. So some people I have an MHC type that selects for really good robust organisms that help them fight off salmonella really well, whereas other people might select for organisms that don't allow them to fight off salmonella very well. The same could be true for some . . . that's why some people get inflammatory bowel disease, some people don't, is you're selecting for just different cohorts of microbes.

Certain MHC types are associated with certain infections. Now, people always thought that that was because the immune system was presenting a better suite of antigens and mounting a better immune response. That's what has been thought for decades and decades, so our findings suggest that it's beyond that actually, it's that the MHC is selecting for microbial communities and some microbial communities are better at helping us battle infection.

Interviewer: I've been learning about certain companies that are making so called poop pills, where they take healthy donors and offer those as fecal transplants for, I think, right now it's mostly for people affected with the sedate. But what you're saying is that if they did an additional screening step it may help those therapies work better.

Dr. Round: Yes, I think for things like infections where the infection lasts a week, it's a very short time frame. I think that the best thing to do would be take it from a very resistant person, resistant to that particular infection because they probably have microbes that are able to fight the infection off.

In our case we were testing salmonella infection. Now, if you want to think about the broader picture, the implications of our findings, although I will say that we haven't quite tested it, is that perhaps for more chronic diseases like inflammatory bowel disease you might have to MHC match for microbes.

Interviewer: The MHC complex and what it does is the same system for like graft versus host when you donate a kidney for example you have to make sure that you have a match.

Dr. Round: That is exactly right.

Interviewer: And if you mismatch then you reject that graft.

Dr. Round: The one thing that's becoming evident is that you can give probiotics to people. You can give them millions and millions of bacteria in a little pill, but it doesn't always stick in the gut. It kind of gets flushed through. And part of that could be because that person doesn't have immune system that selects and allows for that bacteria to live there.

The same is true for fecal transplants. A lot of times to give a fecal transplant to someone and it works for a little bit, it stays in the gut of those people for a little bit, but then eventually those organisms get either competed out, flushed out, they're just not selected for.

So our findings suggest that perhaps we can make fecal transplants stick a little bit better if maybe we match the MHC donor to a recipient. We keep talking about this idea of personalized medicine and I think as far as personalized medicine is concerned, we're going to have to couple the genetics of the person, which is going to include the genetics, their immune profiles as well.

We're going to have to couple the genetics with the person along with the types of microbial communities. I think if in the future we can put those two together that we can have some really powerful therapeutic interventions in the future.

Announcer: Interesting, informative, and all in the name of better health. This is The Scope, University of Utah Health Radio.